ROSENBLUM ESSAY

Frye Art Museum catalogue for exhibition in 2000

REINVENTING MYTH

Although one history of modern art tells us how painting and sculpture were reborn by shedding the skin of the past, many other histories remain to be told. Looking backward from the dawn of the twenty-first century, we can see, for example, that the huge and weighty heritage of the old masters preserved in museums could be envisioned as a graveyard by young rebels who hated the past and hoped for a totally different future. But this burden of history could also be rejuvenated in unexpected ways. Picasso himself, while shattering one canon after another, kept invoking such Olympian deities as El Greco and Rembrandt, Ingres and Manet. And many artists who participated in the upheavals of the early twentieth century would later turn their backs entirely on the spirit of innovation, returning, like de Chirico, to standards inspired by the likes of Tintoretto, Canaletto, or Courbet. And if we thought that with the advent of Impressionism, nymphs and satyrs, centaurs and minotaurs had become endangered species, we now realize, when looking at Matisse or Picasso, that even those mythical creatures could survive the thrilling deluge of modernism.

So it is that, in broader retrospect, a painter like Lisa Zwerling, whose canvases at first may look as if they belong to any century but the twentieth, is hardly an anachronism at all, but yet another example of someone who is trying to resurrect, in completely personal ways, the magic of those old masters who could make us believe that Daphne could turn into a tree or that Icarus’s waxen wings were melted by the sun. For a contemporary artist, living in a world where Bulfinch’s "Mythology" has disappeared from classrooms and the impalpable electronic images that appear on a screen have more reality than the physical succulence of pigment on canvas, this no easy job. Zwerling, for one thing, is immersed in the sensuous universe of old master paintings, almost wallowing in the pleasures Titian’s and Rubens’s brushwork and hoping in some way to revitalize their technical prowess. But she is no less fascinated by these masters’ ability to use their craft as a language of ancient emotional truths. For her, artists as diverse as Piero de Cosimo and Henri Rousseau can present models of narrative mystery in works that make us feel the overwhelming power of some awesome thing called nature, from which we are all born and into which we will all disappear.

This, in fact, is Zwerling’s presiding theme. Her pictorial theater rushes us light-years away from the present tense of urban life – she is, after all, firmly installed in a New York Soho loft – to an imaginary domain populated by wild animals and by men and women as remote and as naked as Adam and Eve or Venus and Adonis. As for the landscapes they, too, regress to the kind of primeval forests, waters, and skies that could illustrate the Book of Genesis. "Sunrise," one of the most recent works in this exhibition’s decade-long anthology of Zwerling’s feverish visions, is a useful introduction to her imaginary universe.

In a related painting of 1999, "Sunset with Fireworks," violence and catastrophe take over. Now the optimistic dawn is replace by an apocalyptic vision of explosive darkness. A star-studded sky, catching the sun’s last rays, bursts with a fireworks spectacle that seems to have been unleashed by cosmic forces. An almost camouflaged in the shadows of the foreground is a lion still gnawing on its human prey, the remains of an arm. (Here one recalls Zwerling’s account of how, in her childhood, a reproduction of Delacroix’s "Lion Hunt," with its painter ferocity of man versus beast, left an indelible impression.)

With her instinct for the most fundamental rhythms of nature’s splendor and terror, it was inevitable that Zwerling turn often to the venerable them of the cycles of nature, which, predictably, she reinvented in completely original ways. If, as in "Wild Child," 1993, she depicts a naked infant alone in a dense wood, we feel we are at many thresholds. Is it Adam and Eve’s first child? Is it the infancy all creatures share? Is it a symbol of spring?

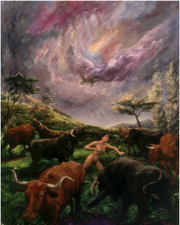

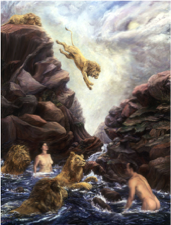

And predictably, Zwerling could also translate the old master narratives of the four seasons into her own symbolic language. In a memorable series dating from 1994-96, we feel that a new version of Ovid’s "Metamorphoses" has been written. "Spring Comet" thrusts us into a wild confusion of sexual awakenings, with a panic-stricken female nude adrift in a raging chaos of bellowing bulls. "Summer Sentinel" brings together a new Adam and Eve, mingling with a pride of lions, one of whom is caught midair in a breathtaking leap from mountain height to foaming water.

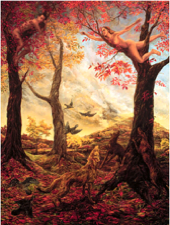

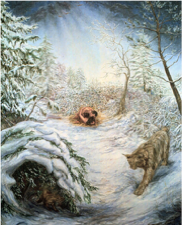

In "Fall Flight," autumn finds the couple separated, but still longing toward each other, locked in the branches of withering trees that seem to sap them of their human strength. And "Winter Passion," the most arresting of the series, finds the naked pair copulating in the middle of a snow-covered forest, their flesh and passion promising the continuity of the relentless rhythms of nature.

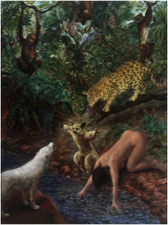

At other times, as in the series of 1997, Zwerling can unfold this four-part cycle in a more traditional sequence of landscape paintings, but here, too, she adds unexpected living presences – in each case, a lone human or animal almost camouflaged by its natural setting. Here, as elsewhere, Zwerling’s sense of the specifics of the natural world – whether the burgeoning leaves, the autumn-colored fox (based on her own taxidermic specimen), the calico cat (her own house pet), or the shivering female nude (the artist’s self portrait) – adds to the magic of her transformations. It is telling that in one painting, "Primitive Mysteries I," 1991, she can populate an imaginary landscape with an animated zoo of what seem to be palpable, scientifically accurate creatures, whose pictorial coexistence, however, is a geographic impossibility given the presence, say, of both an Arctic wolf and an African bush baby. Here one may recall Marianne Moore’s famous definition of poetry as “real toads in imaginary gardens.”

Robert Rosenblum was Professor of Fine Arts at New York University and a curator at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Among his publications are "The Romantic Child from Runge to Sendak" (1988) and "Paintings in the Musee d’Orsay" (1989). He is the co-author, with H. W. Janson, of the major reference work "19th - Century Art." Professor Rosenblum has also published books on contemporary artists Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol.

At the left, a female nude, protected by a primitive fur blanket, awakens on the top of a verdant hill. Crowning the hill is the stark silhouette of a blasted tree, on which a gorgeously plumed African bird perches, heralding, it would seem, a blazing sunrise that feels like the dawn of a new era in prehistory. For the figure of this lone, primordial woman, a survivor perhaps of an earlier disaster, Zwerling found inspiration in a diorama at the Brussels Museum of Natural History that included the model of a Neanderthal woman huddling under the warmth of an animal skin. Characteristic of Zwerling’s leaps from fact to fiction, the scientific display triggered this mythical voyage in time. The museum model was unexpectedly reincarnated as an ancient human presence waking to an all-embracing nature that for the moment may look benevolent but, as we know from other canvases, could suddenly become an agent of cataclysm.

That we are coerced into reading this as an awesome awakening to a freshly fertile world has to do not only with Zwerling’s uncommon ability to turn any fact into a fresh narrative from her dreamlike mythology, but with her equally uncommon gift at resurrecting the organic energies of old master landscape painting. Here, the grassy bank on which the primitive human heroine has been sleeping seems seeped with the kind of sap Rubens had used to make his trees and bushes burst with fresh vitality. The sky, with its sublime expanses of solar yellows and reds against cerulean blues, continues, even in the late twentieth century, to elicit the quasi-religious faith in nature’s bounties and powers that marked the heavens of such artist-deities in Zwerling’s pantheon as J. M. Turner or his American counterpart, Frederic E. Church. But nature has no morality, and can be mindlessly brutal.

A third painting in this group, "Forest Fire," pushes even closer to the brink of total disaster. A resplendent peacock, poised on a high branch, calmly observes the hellish flames around him that engulf a once fertile forest and threaten his own life. The contrast between serene natural beauty and agonized destruction is both startlingly simple and uncannily strange, a potent instance of Zwerling’s gift of rediscovering archetypal images and emotions. A visit to her studio discloses some of her material inspiration, in this case, a stuffed peacock, one of the many taxidermic trophies she lives with. Through her use of the peacock, now animated by a wealth of colored pigment and paired with a raging fire, Zwerling not only probes deeply into an evocative domain of allegory, with musings on the transience of beauty and the cycles of nature, but into more emotive terrains that, as in a nightmare, can illuminate for a moment the artist’s personal traumas, whether a medical or a psychological crisis. But most importantly, these records of private turmoil are completely transformed into a public language that instantly registers a sense of overwhelming peril. Such anxieties are given terrifying immediacy in "Fire," 1998, in which two foxes on the edge of precipice watch a human creature fall, like Icarus, from the sky towards a bonfire. Turned in on itself like a fetus, this mythical nude plummets to an instant cremation.

As singular and personal as Zwerling’s mythic inventions may be, her work should also be perceived as one aspect of the resurgence of representational painting in the later twentieth century. For one thing, there is her total commitment to embracing the art of the past, a phenomenon that, for want of a better work, can be described as post-modernist and one that is shared in various ways by artists all over our planet. Whether in paint or photography, these artists would recreate everything from Leonardo and Rembrandt to Duchamp and Picasso. There is also Zwerling’s passion for filling the void left by a dying biblical and classical tradition with new myths. Such adventurous pursuits are shared, for one, by the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum (who also exhibited at the Frye Art Museum), and, for another, by Matthew Barney, who, in a different medium – film – also resurrects the visceral experience of being reunited, even in this alien, manmade world, with nature’s magical narratives. Zwerling, like all artists whose work we immediately remember, speaks in her own voice but also belongs to a chorus of contemporaries.

Click to enlarge images

ROBERT ROSENBLUM